About the Commemoration

Martin Luther King Jr., who led the first mass civil rights movement in the United States, was born January 15, 1929, in Atlanta, Georgia. An exceptional student, he entered Morehouse college in Atlanta at the age of fifteen under a special program and earned his B.A. in 1948. His earlier interests in medicine and law gave way to a decision to enter the ministry. He entered Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania, where he studied Gandhi’s philosophy of nonviolence. King was elected president of the student body and graduated from the seminary in 1951. He then went to Boston University where he met Coretta Scott, who was a student at the New England Conservatory of Music. They married in 1953. King received the Ph.D. from Boston University in 1955. He became pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama, and while he was there, a group decided to challenge racial segregation of public busses. On December 1,1955, Mrs. Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a bus to a white passenger and was arrested for violating the city’s segregation law. The Montgomery Improvement Association was formed, and King was named its leader. His home was dynamited and his family threatened, yet he held fast. In a year, desegregation was accomplished. To capitalize on the success in Montgomery, King in 1957 organized the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, which gave him a base of operation and a national platform.

In 1960 he moved to Atlanta to become co-pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church with his father. In October 1960 he was arrested for protesting the segregation of the lunch counter in a department store in Atlanta. The years 1960 to 1965 marked the height of his influence. Although not always successful, the principle of nonviolence aroused the interest of many blacks and whites. In the spring of 1963, he was arrested in a campaign to end the segregation of lunch counters in Birmingham, Alabama. The police had turned fire hoses and dogs on the demonstrators and thus brought the incident to national attention. Some of the clergy of the city had issued a statement urging the citizens not to participate in the demonstrations, and King responded eloquently in his Letter from Birmingham Jail.

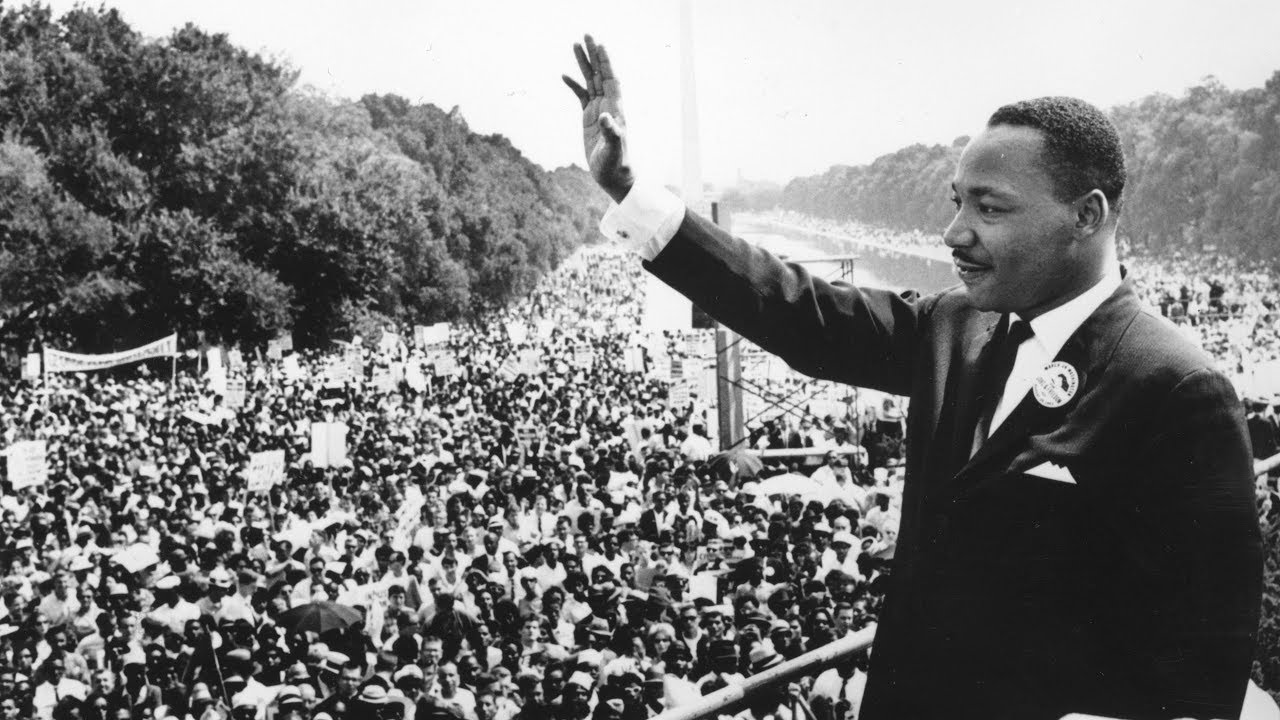

On August 28, 1963, two hundred thousand people marched on Washington in a peaceful assembly at the Lincoln Memorial and heard King’s emotional and prophetic speech known as “I have a dream.” The Civil Rights Act, passed later that year, authorized the federal government to enforce the desegregation of public accommodations and outlawed discrimination in publicly owned facilities and in employment. Also in 1964 Martin Luther King Jr. was awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace for his application of the principle of nonviolent resistance in the struggle for racial equality.

King broadened his concern to include not only justice between the races but justice between the nations as well. In January 1966 he condemned the war in Vietnam, and his attack was renewed on April 4, 1967, at Riverside Church in New York and on April 15 at a huge rally for peace.

King had planned a Poor People’s March on Washington but interrupted his plans in the spring of 1968 to travel to Memphis, Tennessee, in support of striking sanitation workers. On April 4, while standing on the balcony of a motel where he was staying, he was shot and killed by a sniper.

By his eloquent and often prophetic preaching, Martin Luther King Jr. called the United States to a new commitment to the ideal of justice, while at the same time consistently resisting the temptation to violence, even when provoked. Struggling against two sides at once—the status quo on the one hand and racial revolution on the other—he taught by word and example the value of what he liked to call “redemptive suffering,” bringing the crucifixion into relation to modern society. He spoke God’s word to a complacent nation, moving it toward the realization of the kingdom of God.

The birthday of Martin Luther King Jr. has been made a civil holiday in the United States, and for that reason the Lutheran Book of Worship set his commemoration on January 15. Because the observance of that federal holiday was in 1986 set on the third Monday in January, the observance of the religious commemoration on April 4, the date of his death, as is customary with commemorations and as observed in the Episcopal Lesser Feasts and Fasts 1997 and in the Methodist For All the Saints, seems perhaps preferable.

Excerpts from New Book of Festivals & Commemorations: A Proposed Common Calendar of Saints by Philip H. Pfatteicher, copyright, 2008 by Fortress Press, an imprint of Augsburg Fortress.

See also: Martin Luther King Jr.

Reading

From Letter from Birmingham Jail by Martin Luther King Jr., April 16, 1963

I, along with several members of my staff, am here because I was invited here. I am here because I have organizational ties here.

But more basically, I am in Birmingham because injustice is here. Just as the prophets of the eighth century B.C. left their villages and carried their “thus saith the Lord” far beyond the boundaries of their home towns, and just as the Apostle Paul left his village of Tarsus and carried the gospel of Jesus Christ to the far comers of the Graeco-Roman world, so am I compelled to carry the gospel of freedom beyond my home town. Like Paul, I must constantly respond to the Macedonian call for aid.

Moreover, I am cognizant of the interrelatedness of all communities and states. I cannot sit idly by in Atlanta and not be concerned about what happens in Birmingham. Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly. Never again can we afford to live with the narrow, provincial “outside agitator” idea. Anyone who lives inside the United States can never be considered an outsider anywhere within its bounds….

My friends, I must say to you that we have not made a single gain in civil rights without determined legal and nonviolent pressure. Lamentably, it is an historic fact that privileged groups seldom give up their privileges voluntarily. Individuals may see the moral light and voluntarily give up their unjust posture; but, as Reinhold Niebuhr has reminded us, groups are more immoral than individuals.

We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given up by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed. Frankly, I have yet to engage in a direct-action campaign that was “well timed” in the view of those who have not suffered unduly from the disease of segregation. For years now I have heard the word “Wait!” It rings in the ear of every Negro with a piercing familiarity. This “Wait” has almost always meant “Never.” We must come to see, with one of our distinguished jurists, that “justice too long delayed is justice denied.”

We have waited for more than 340 years for our constitutional and God-given rights. The nations of Asia and Africa are moving with jetlike speed toward gaining political independence, but we still creep at horse-and-buggy pace toward the gaining of a cup of coffee at a lunch counter. Perhaps it is easy for those who have never felt the stinging darts of segregation to say, “Wait.” But when you have seen vicious mobs lynch your mothers and fathers at will and drown your sisters and brothers at whim; when you have seen hate-filled policemen curse, kick and even kill your black brothers and sisters; when you see the vast majority of your twenty million Negro brothers smothering in an airtight cage of poverty in the midst of an affluent society’; when you suddenly find your tongue twisted and your speech stammering as you seek to explain to your six-year old daughter why she can’t go to the public amusement park that has just been advertised on television, and see tears welling up in her eyes when she is told that Funtown is closed to colored children, and see ominous clouds of inferiority beginning to form in her little mental sky, and see her beginning to distort her personality by developing an unconscious bitterness toward white people; when you have to concoct an answer for a five-year old son who is asking: “Daddy, why do white people treat colored people so mean?”; when you take a cross-country drive and find it necessary to sleep night after night in the uncomfortable corners of your automobile because no motel will accept you; when you are humiliated day in and day out by nagging signs reading “white” and “colored”; when your first name becomes “nigger” and your middle name becomes “boy” (however old you are) and your last name becomes “John,” and your wife and mother are never given the respected title “Mrs.”; when you are harried by day and haunted by night by the fact that you are a Negro, living constantly at tiptoe stance never quite knowing what to expect next, and plagued with inner fears and outer resentments; when you are forever fighting a degrading sense of “nobodiness”—then you will understand why we find it difficult to wait. There comes a time when the cup of endurance runs over, and men are no longer willing to be plunged into the abyss of despair. I hope, sirs, you can understand our legitimate and unavoidable impatience.

Martin Luther King Jr., “A letter from Birmingham Jail” in Why We Cant Wait is reprinted by arrangement with The Heirs to the Estate of Martin Luther King, Jr., c/o Writers House, Ina as agent for the proprieter. Copyright © 1963 by Martin Luther Kint Jr., copyright renewed 1991 by Coretta Scott King.

Propers

Holy and righteous God, you created us in your image. Grant us grace to contend fearlessly against evil and to make no peace with oppression. Help us, like your sen ant Martin Luther King, to use our freedom to bring justice among people and nations, to the glory of your Name; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and forever.

BCP, rev. LBW, ELW Common of Renewers of Society

Readings: Exodus 3:7-12; Psalm 77:11-20 or 98:1-4; Romans 12:9-21; Luke 6:27-36

Hymn of the Day: “Judge eternal, throned in splendor” (LBW 418, H82 596); “Lift every voice and sing” (LBW 562, LSB 964, ELW 841, H82 599) (the African American anthem)

Prayers: For peace For social justice; For grace to learn that voluntary suffering can be redemptive; For a quickening of the national conscience.

Preface: Baptism (BCP, LBW)

Color: Red