About the Commemoration

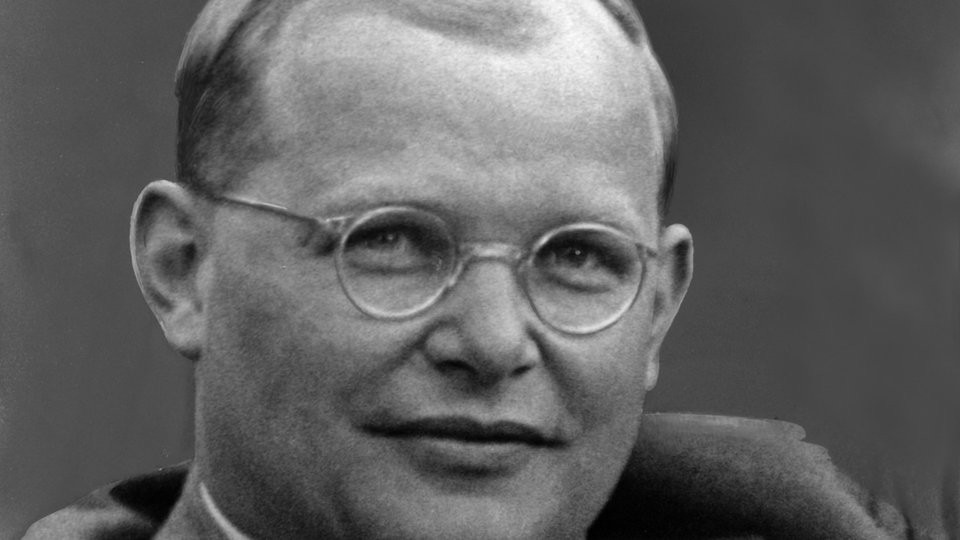

Dietrich Bonhoeffer was born in Breslau February 4,1906, and grew up in the university circles of Berlin, where his father Karl was professor of psychiatry and neurolog)’. He studied at the universities of Berlin and Tubingen from 1923 to 1927; his doctoral thesis was published in 1930 as Communio Sanctorum (“The Communion of Saints”). From 1928 to 1933 he was the assistant pastor of a German-speaking congregation in Barcelona. He then spent a year as an exchange student at Union Seminary in New York City and returned to Germany in 1931 to lecture in systematic theology at the University of Berlin.

From the first days of the Nazi accession to power in 1933, Bonhoeffer was involved in protests against the regime, especially its anti-Semitism. From 1933 to 1935 he was the pastor of two small German congregations in London but nonetheless was a leading spokesman for the Confessing Church, the center of Protestant resistance to the Nazis. In 1935 Bonhoeffer was appointed to organize and head a new seminary at Finkenwald, which continued in a disguised form until 1940. He described the community in Life Together (1939; English translation 1954, 1997). Out of his struggle also came his best-known book, The Cost of Discipleship (1948; English translation 1959, 2001), which attacked the notion of “cheap grace,” an unlimited offer of forgiveness that masked moral laxity.

The Bishop of Chichester, G. K. A. Bell, became interested in efforts to interpret the Church struggle (Kirchenkampf) and became a friend of Bonhoeffer. Bonhoeffer’s own involvement became increasingly political after 1939, when his brother-in-law introduced him to the group seeking Hitler’s overthrow. In 1939 Bonhoeffer considered refuge in the United States, but he returned to Germany where he was able to continue his resistance as an employee of the Military Intelligence Department, which was a center of resistance. In May of 1942 he flew to Sweden to meet Bishop Bell and convey through him to the British government proposals for a negotiated peace. The Allies rejected the offer, who insisted upon unconditional surrender.

Bonhoeffer was arrested April 5, 1943, and imprisoned in Berlin (he had just announced his engagement to be married). After an attempt on Hitler’s life failed April 9, 1944, documents were discovered linking Bonhoeffer to the conspiracy. He was taken to Buchenwald concentration camp, then to Schönberg prison. On Sunday, April 8, 1945, just as he concluded a service in a school building in Schönberg in the Bavarian forest, two men came in with the chilling summons, “Prisoner Bonhoeffer, come with us.” As he left, he said to Payne Best, an English prisoner who described the event in The Venlo Incident, “This is the end. For me, the beginning of life.” Bonhoeffer was hanged the next day, April 9, 1945, at Flossenburg prison.

When Bonhoeffer was included on the calendar in the Lutheran Book of Worship he was not described as a martyr because of some hesitation both in Germany and in America, since he was killed not for his adherence to the Christian faith but for his political activities against the German government. In Lesser Feasts and Fasts, which now lists him, he is called “Pastor and Theologian” but not “Martyr.” The reluctance to call him a martyr, however, has largely dissipated in the face of the recognition that his resistance was rooted clearly in his Christian commitment. (A Berlin court ruled in 1996 that Bonhoeffer was innocent of high treason.) The German Evangelical Calendar of Names lists him as “Martyr in the Church Struggle,” and there is in Bonhoeffer’s life a remarkable unity of faith, prayer, writing, and action. The pacifist theologian came to accept the guilt of plotting the death of Hitler because he was convinced that not to do so would be a greater evil. Discipleship was to be had only at great cost.

Bonhoeffer was included on the calendar in the Lutheran Book of Worship and was added to the Episcopal calendar in Lesser Feasts and Fasts 1997, and is on the calendar in the Methodist book For All the Saints.

In remembering key figures in important religious and social movements such as Bonhoeffer or Martin Luther King Jr., one needs to keep in mind that these people are representatives who both clarify and have been nourished by the struggle of countless more obscure people who were no less brave in their witness.

Excerpts from New Book of Festivals & Commemorations: A Proposed Common Calendar of Saints by Philip H. Pfatteicher, copyright, 2008 by Fortress Press, an imprint of Augsburg Fortress.

See also: Dietrich Bonhoeffer

Reading

From a letter by Dietrich Bonhoeffer

I often ask myself why a “Christian instinct” often draws me more to the religionless people than to the religious, by which I don’t in the least mean with any evangelizing intention, but, I might almost say, “in brotherhood.” While I’m often reluctant to mention God by name to religious people—because that name somehow seems to me here not to ring true, and I feel myself to be slightly dishonest (it’s particularly bad when others start to talk in religious jargon; I then dry up almost completely and feel awkward and uncomfortable)—to people with no religion 1 can on occasion mention him by name quite calmly and as a matter of course. Religious people speak of God when human knowledge (perhaps simply because they are too lazy to think) has come to an end, or when human resources fail—in fact it is always the deus ex machina that they bring on the scene, either for the apparent solution of insoluble problems, or as strength in human failure—always, that is to say, exploiting human weakness or human boundaries. Of necessity, that can go on only till people can by their own strength push those boundaries somewhat further out, so that God becomes superfluous as a deus ex machina. I’ve come to be doubtful of talking about any human boundaries (is even death, which people now hardly fear, and is sin, which they now hardly understand, still a genuine boundary today?). It always seems to me that we are trying anxiously in this way to reserve some space for God; I should like to speak of God not on the boundaries but at the center, not in weakness but in strength; and therefore not in death and guilt but in man’s life and goodness. As to the boundaries, it seems to me better to be silent and leave the insoluble unsolved. Belief in the resurrection is not the “solution” of the problem of death. God’s “beyond” is not the beyond of our cognitive faculties. The transcendence of epistemological theory has nothing to do with the transcendence of God. God is beyond in the midst of our life. The church stands, not at the boundaries where human powers give out, but in the middle of the village. That is how it is in the Old Testament, and in this sense we still read the New Testament far too little in the light of the Old. How this religionless Christianity looks, what form it takes, is something that I’m thinking about a great deal, and I shall be writing to you again about it soon. It may be that on us in particular, midway between East and West, there will fall a heavy responsibility.

From a letter to Eberhard Bethge (30 April 1944) from Tegel prison, in Letters and Papers from Prison, enlarged ed., ed. Eberhard Bethge (New York: Macmillan, 1971), 281-82.

Propers

Gracious Lord, the Christian faith of your servant Dietrich Bonhoeffer impelled him to defy the forces of darkness, to protest the evil of anti-Semitism, and finally, fearing not death but rather the greater evil of tolerating oppression, to lay down his life in witness to your rule: Grant us the same Spirit of courage to resist tyranny in all its forms and the strength to follow Christ into unfamiliar places, knowing that, whether we live or die, we are with you; through your Son Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and forever.

PHP

Readings: Proverbs 3:1-7; Psalm 119:89-96; Revelation 6:9-11; Matthew 13:47-52

Hymn of the Day: “God of grace and God of glory” (H82 594, 595; LBW 415, LSB 850, ELW 705)

Prayers: For a deepened discipleship; For courage to resist tyranny in all its forms; For strength to pay the price of following Christ into places where we are beyond familiar rules; For those whose names are not remembered who with Bonhoeffer resisted tyranny.

Preface: A Saint (3) (BCP)

Color: Red